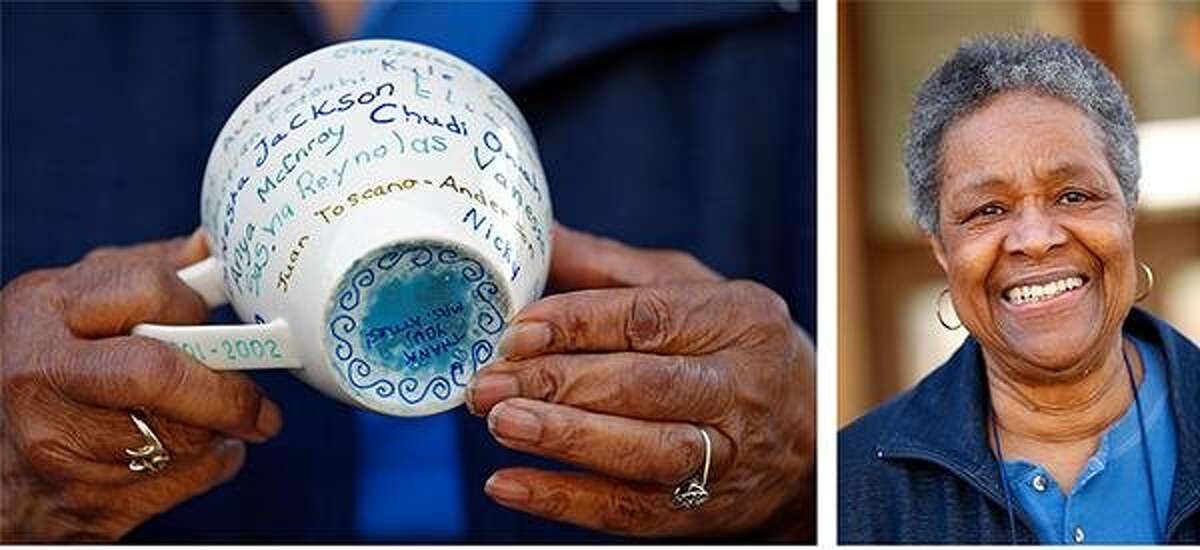

Retired teacher Wilhelmina Attles was cleaning her kitchen last month when she came across a coffee mug adorned with signatures from one of her old third-grade classes at Montclair Elementary School.

Toward the bottom of the cup was a familiar name in green marker: Juan Toscano-Anderson, now a 6-foot-6, 213-pound backup forward for the Golden State Warriors who has become a fan favorite.

But when Toscano-Anderson first arrived at Mrs. Attles’ classroom in cornrows and a Larry Hughes replica Warriors jersey, he was an 8-year-old from the urban flatlands of East Oakland in a room filled with children from the more affluent Oakland hills.

Wilhelmina, the wife of Golden State legend Al Attles, could sense that something troubled her new student. There was a sadness in his eyes. In class, his voice barely rose above a whisper.

What Attles didn’t know then was that Toscano-Anderson was homeless. Some nights, he slept with his mom, Patricia Toscano, and sister, Ariana, in their silver sedan.

Willhemina Attles, wife of Warriors’ Hall of Famer Al Attles, holds a mug signed by current Warrior Juan Toscano-Anderson and his 3rd grade classmates from back in 2002 when Attles was Toscano-Anderson’s teacher at Montclair Elementary School in Oakland, Calif.. Photographed outside the school on Monday, March 1, 2021.

Scott Strazzante / The ChronicleBut on the blacktop at recess, Toscano-Anderson forgot all about the outside world. For those 20 or so minutes, he was like any other kid, giggling as he beat his classmates in footraces or pickup basketball games.

When Attles arranged for him to attend the Warriors’ youth basketball camp for free, she didn’t imagine that it would start a hardwood odyssey that would culminate in a roster spot on his hometown NBA team. All she wanted was to keep him smiling.

“As a teacher, you spend so much time around these kids that you know what they need at various times,” said Attles, who watches every Warriors game to cheer for Toscano-Anderson. “At that time, I could see that Juan loved sports. He needed an outlet.”

Toscano-Anderson would require resilience, a change in the NBA’s style of play and some luck to go from a seldom-used college reserve to a rotation player with the Warriors. The lone constant during a journey that included stops in Mexico and Santa Cruz was his unparalleled effort. Now, at 27, he is drawing comparisons to All-Star teammate Draymond Green for his court vision and energy.

“Some players play hungry; Juan plays like a guy who’s starving,” Warriors guard Mychal Mulder said. It’s a reflection of Toscano-Anderson’s upbringing in East Oakland, the most dangerous area of a city with 30 homicides already in 2021.

Golden State Warriors forward Juan Toscano-Anderson (95) looks to pass while defended by Charlotte Hornets forward Cody Martin (11) during an NBA game at Chase Center, Friday, Feb. 26, 2021, in San Francisco, Calif.

Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle“Coming up in the part of the town that I came up in, it almost feels like you’re in that book, ‘Where the Wild Things Are,’ ” Toscano-Anderson said. “You’re running into all these different monsters, only they’re things like gangs and drive-by shootings.”

Patricia Toscano, who grew up in a neighborhood known to locals as “the killing zone,” often worried that her four kids were destined to become grim statistics. Her younger brother, a nephew and two of her cousins were all shot and killed in East Oakland.

By the time Juan was 14, Patricia’s goal for him was clear: college — somewhere, anywhere — and a life away from Oakland. What she couldn’t have foreseen was that Juan would travel the world, only to return to the Bay Area and offer hope to the next generation of Oaklanders.

“I always knew he’d be a statistic,” Patricia said. “I’m just ecstatic that he’s one of the positive ones. To see your child living his dream, it means everything.”

Patricia Toscano, mother of Golden State Warriors forward Juan Toscano-Anderson, stands outside his childhood home in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, Feb. 28, 2021.

Noah Berger / Special to The ChronicleToscano-Anderson’s No. 95 jersey, the highest number in Warriors history, is a nod to his grandfather’s home at 95th Avenue and A Street in East Oakland’s Elmhurst neighborhood.

That yellow, single-story house with a lime tree in the front yard has long been a family haven. When Patricia’s salary from teaching violence-prevention skills to juvenile offenders wasn’t enough to cover the rent, she and her kids stayed with her father, Macario Toscano. There, in the back of the driveway, Juan and his cousins would shoot at a plastic crate hung on a gate.

Macario had bought the house in 1970 after moving to Oakland, where a couple of his sisters had settled, from the Mexican state of Michoacán. A mechanical engineer, he raised four kids as a single father and tried to shield them from the gang violence overtaking the surrounding streets.

One night in July 1992, Macario’s youngest son, Juan, had an argument with someone in the neighborhood. After police officers broke up the dispute and left the scene, the man returned. He shot and killed Juan on 92nd Avenue. He was just 19.

Though Patricia was three years older, she had viewed Juan as her protector. Whenever issues arose in the neighborhood, it was Juan who defended her. Without him, she felt lost.

A week before Juan was killed, Patricia had learned she was pregnant with her second child. Her doctor told her she was having a girl. Patricia, still grieving the death of her younger brother, sank into a deep depression. She missed doctor’s appointments.

Seventeen days after her due date, Patricia went into labor. To her surprise, she was having a boy. But there were complications. The doctor asked Patricia’s family whom he should save, if it came down to a choice: mother or son.

After 3½ hours of labor, Patricia gave birth to a 9-pound, 12-ounce baby. She named him Juan.

“He’s had a fighting spirit since the moment he came into the world,” Patricia said. “At one point, the doctor thought they might not be able to save either one of us. But hey, he’s here and I’m here. He’s here, and he’s making his presence felt.”

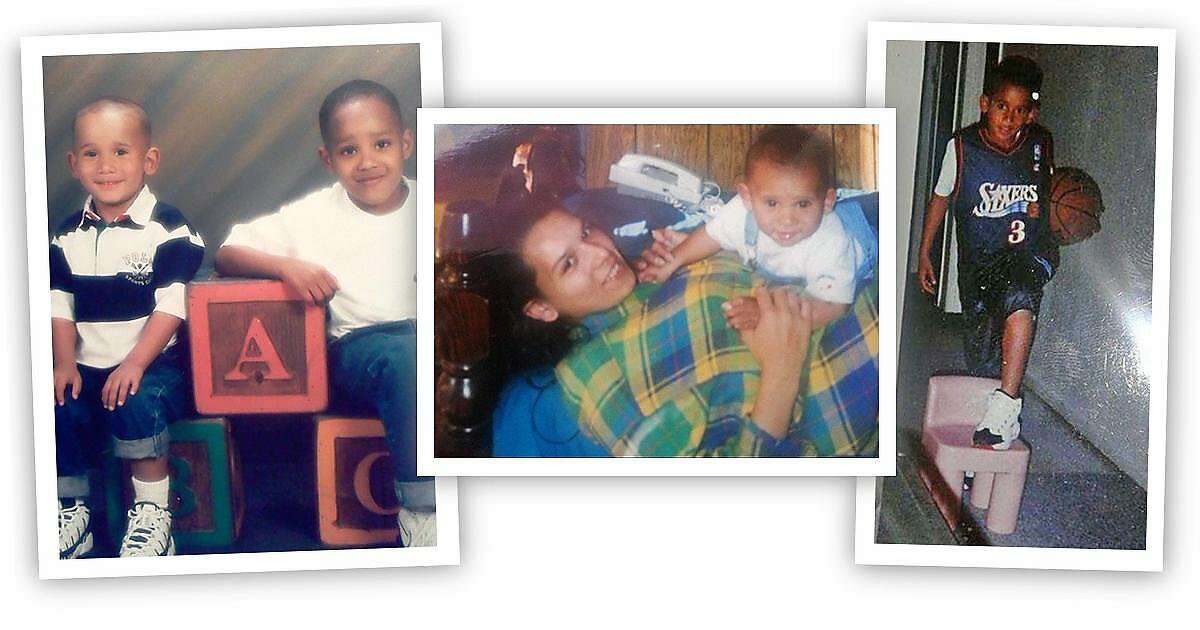

As a kid, Toscano-Anderson lived in five houses scattered across East Oakland. When he was 7, his mom saved enough money to relocate to Castro Valley, a suburb free of many of her old neighborhood’s hardships.

But just three months after Patricia moved in, the house she was renting burned down in an electrical fire in the middle of the night while Juan and Ariana were at a slumber party. Almost all their belongings, including many of the kids’ childhood photos, were destroyed.

For the next year, Patricia and her two youngest kids ping-ponged between relatives’ houses and budget motels, unsure where they’d sleep most nights. One family member who took them in for a period had a rule: Everyone needed to be out of the house by the time she left for work at 4 a.m.

For the four hours before Patricia could drop her kids off at school, she watched as Juan read children’s books to his little sister and sang songs in their sedan. On a handful of chilly nights, when Patricia couldn’t afford a motel and no relatives had a spare room, she slept in the passenger seat while Juan and Ariana were in the back, their blankets pulled tight.

Family photos from Juan Toscano-Anderson’s youth.

Courtesy Patricia ToscanoAround this time, a student in Juan’s third-grade class at Stonehurst Elementary School in East Oakland threatened to stab him. Using her sister’s address, Patricia transferred Juan to Montclair — only a 15-minute drive from Elmhurst, but a world away in some respects. Many of Juan’s new classmates had parents who were doctors or lawyers.

Attles, one of Montclair’s only African American teachers, felt an immediate kinship with Juan, who is half-Black, half-Mexican. A month after Juan enrolled at Montclair, Attles learned from a member of the parent-teacher association that Juan had been staying at a family member’s house over the holidays when an intruder shot and killed one of Juan’s relatives, then stole the Christmas presents from under the tree.

Attles worked with the PTA to raise money to replace all the stolen gifts. For the rest of the school year, she made herself available to Juan anytime he needed her.

“We were just so hurt, the staff and I, that a kid would be exposed to that,” Attles said. “After that happened, I was just really aware that he needed me more than I had thought when he first came to school. I tried to provide a shoulder, just extra love and attention.”

In addition to sending Juan to the Warriors’ youth basketball camp, Attles connected him with the Oakland Rebels, a youth AAU program. Teacher and student lost touch, however, when he moved on to Montera Middle School.

As the years passed, Attles often wondered what had become of the meek boy with the cornrows and the Larry Hughes jersey. Friends told her that he had blossomed into an all-state player at Castro Valley High School. Beyond that, Attles didn’t know much.

Then, one day in spring 2015, Attles received a small package containing a program from the Marquette University men’s basketball program and a letter. It was from Patricia Toscano. She thanked Attles for all she’d done for Juan in third grade and told her that he was about to graduate from Marquette with a bachelor’s degree in criminology.

“None of this would’ve been possible without your love and support at a very difficult time in our lives,” Patricia wrote. “We will forever be grateful.”

Golden State Warriors’ Juan Toscano-Anderson disputes fouling Miami Heat’s Jimmy Butler in 1st quarter during NBA, basketball game at Chase Center in San Francisco, Calif., on Wednesday, February 17, 2021.

Scott Strazzante / The ChronicleAlmost every off day the Warriors get, Toscano-Anderson guides his Honda east on Interstate 580, toward the streets where he learned the power of perseverance.

“I paint the city, man,” Toscano-Anderson said. “I hit all my spots.”

After visiting his mom in San Leandro and getting a trim at Phat Fades Barbershop on East 14th Street, he stops by his grandpa’s house on 95th Avenue. Before returning to his luxury apartment near Chase Center in San Francisco, Toscano-Anderson feasts at his favorite Mexican restaurant, Mariscos La Costa on International Boulevard.

As he walks past familiar liquor stores and laundromats, he is reminded of some childhood memories that shake him to this day. The time when he was in the backseat of his mom’s car outside the McDonald’s on 98th Avenue and International as men exchanged gunfire that barely missed him. The time he saw a homeless man beat another homeless man with an aluminum bat on 95th Avenue.

Despite the violence, Toscano-Anderson came to appreciate East Oakland’s blue-collar ethos at an early age. When his mom moved back to Castro Valley when he was in fifth grade, he refused to leave East Oakland. Even then, he knew that suburbia didn’t suit him.

Through the rest of elementary and middle school, Juan split time between his grandpa’s home and those of his AAU coaches in Oakland, not moving to Castro Valley full-time until the summer before his freshman year of high school.

Golden State Warriors forward Juan Toscano-Anderson’s uncle Macario Toscano, Jr. takes a photo with family members outside Toscano-Anderson’s childhood home in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, Feb. 28, 2021. From left to right are Macario Toscano, Jr., Ryan Toscano and Sandra Toscano.

Noah Berger / Special to The ChronicleDuring the first few months in his new town, he took care of his two younger siblings while his mom worked as the director of Catholic Charities’ violence prevention program. One night, Raymond Young, the Oakland Rebels’ head coach, called Patricia and told her to make other babysitting arrangements. Juan, he said, had a real future in basketball.

Fueled by the desire to land a college scholarship and help his mom, Toscano-Anderson blossomed into a four-star recruit. In the fall of his senior year at Castro Valley, he committed to Marquette. His top choice was Cal in nearby Berkeley, but his mother, desperate for him to get as far away from East Oakland’s streets as possible, convinced him to pick the Wisconsin school.

Five months later, one of his closest cousins, Eric Toscano, was shot and killed while celebrating his 18th birthday at his home on Ney Avenue in East Oakland. John Martinez, an alleged gang member, tried to crash the party and was turned away by Toscano’s father. According to reports, Martinez allegedly returned in a car a half-hour later and opened fire on bystanders, killing Toscano and wounding three other partygoers.

Toscano-Anderson could have been among them. He had planned to attend the party. But after he came home from practice earlier that day complaining of knee pain, Patricia had given him Tylenol with Codeine.

“I knew they’d knock him right out,” Patricia said. “I just didn’t want him to go to the party. I had this feeling that something bad was going to happen.”

During the All-Star break, Juan Toscano-Anderson held a basketball camp at an elementary school in Monterrey, Mexico.

Courtesy of WarriorsToscano-Anderson memorialized his late cousin by getting a tattoo of “78” — Eric’s jersey number with Oakland’s Skyline High School football team — on his upper left arm. On his right shoulder, the words “One in a Million” are written in black ink.

In the decade since Toscano-Anderson got that tattoo as a junior at Castro Valley, he had reasons to believe he might not be so special. After averaging 3.8 points per game over his four-year career at Marquette, Toscano-Anderson didn’t receive a single offer to play overseas, much less in the NBA.

Just as he was starting to contemplate life without basketball, he got a call from the Mexican national team, which wanted to fly him to Mexico City for a tryout. Toscano-Anderson’s performance at the 2015 FIBA Americas championship was enough to land him a contract from Mexico’s top league.

Over the next three years, he established himself as the country’s best player. But he gave up a six-figure salary and a luxury apartment in Monterrey for the chance to join more than two dozen players at a tryout for a training-camp spot with Golden State’s G League affiliate. To make the Santa Cruz Warriors’ 2018-19 roster, Toscano-Anderson needed some good fortune — a timely preseason trade that freed up a contract for him.

His ability to guard multiple positions, find open shooters and ratchet up the tempo intrigued Golden State, which had helped hasten the league’s trend toward a positionless brand of basketball. Now Toscano-Anderson is poised to become the first Oakland-born player since the early 1970s to stick on the Warriors’ roster for three straight seasons.

In 27 games, he has averaged 5.0 points on 53% shooting (37.5% from 3-point range), 4.1 rebounds and 2.1 assists in 19.3 minutes. In addition to becoming a hero of sorts to Mexicans and Mexican Americans for being the only active NBA player of Mexican descent, Toscano-Anderson has become an icon to Oaklanders, many of them still upset that the Warriors left their home of 47 years for San Francisco.

When Toscano-Anderson shops at the Costco in San Leandro, strangers often thank him for organizing two protests in Oakland last spring against social injustice and police brutality. Many in the Elmhurst neighborhood know that, if they need a place to stay while they get their lives back on track, Toscano-Anderson and his mom will try to help provide accommodations.

Even now, 40 games into his NBA career, Toscano-Anderson still finds it hard to believe he’s on the Warriors. After a home game last month, he returned to his apartment with his girlfriend and turned on NBC Sports Bay Area. A “Warriors Outsiders” segment was detailing Toscano-Anderson’s rise with Golden State.

“I was just like, ‘This is insane,’” Toscano-Anderson said. “Everything I envisioned as a young kid, when I met Ms. Attles and I had cornrows and I used to wear a Larry Hughes jersey to school, I’m doing all of that right now. I don’t take any of that for granted.”

Connor Letourneau is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @Con_Chron